January 22, 2026

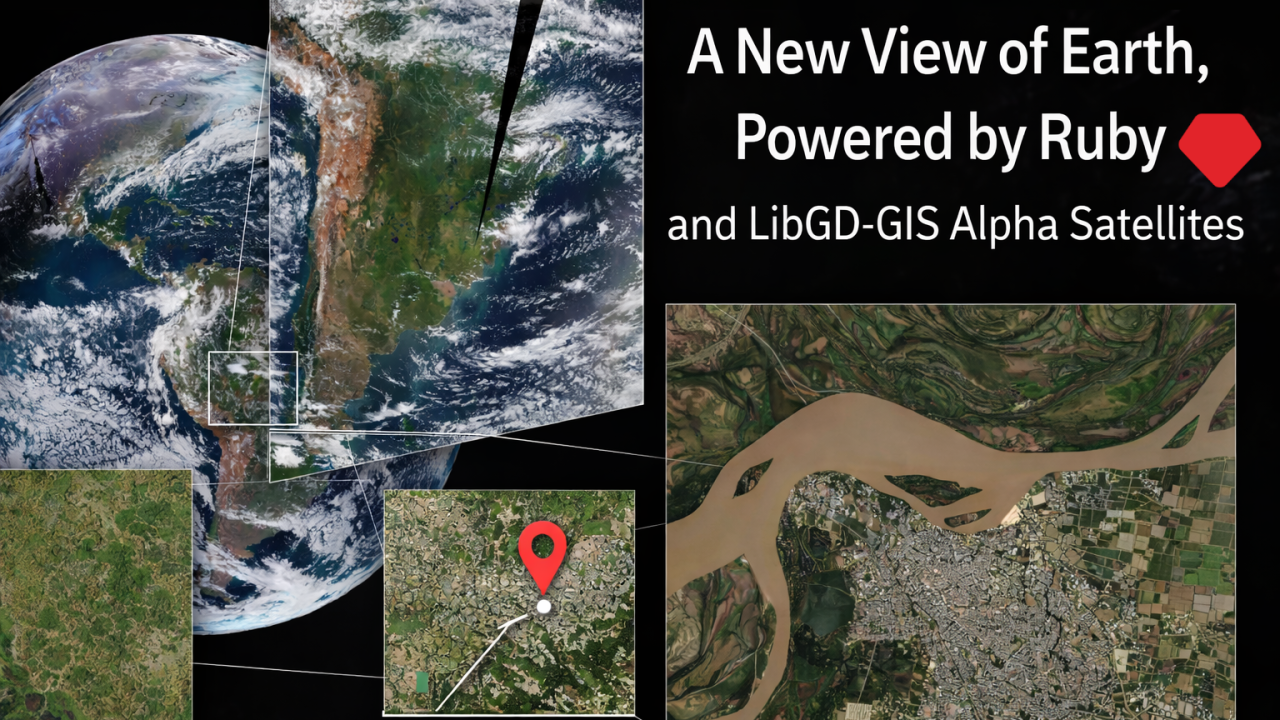

libgd-gis, satellite imagery, and a new way to think about maps

Most mapping libraries start from the same place: roads, labels, vectors, tiles.

But what happens if the map itself is not the goal?

What if the map is just a lens to observe the planet?

This article is about how libgd-gis, a Ruby gem originally designed for cartographic rendering, became a tool to analyze satellite imagery at multiple scales, from the entire hemisphere down to a single river near Paraná, Argentina.

1. The usual mental model: “maps”

Traditionally, maps are:

- vector data (roads, borders, cities)

- raster tiles (OSM, Carto, ESRI)

- fixed zoom pyramids

- stylistic concerns first, data second

Most libraries reflect this mindset.

libgd-gis started exactly there: rendering tiled maps, projecting GeoJSON, styling layers.

But satellite imagery does not behave like classic maps.

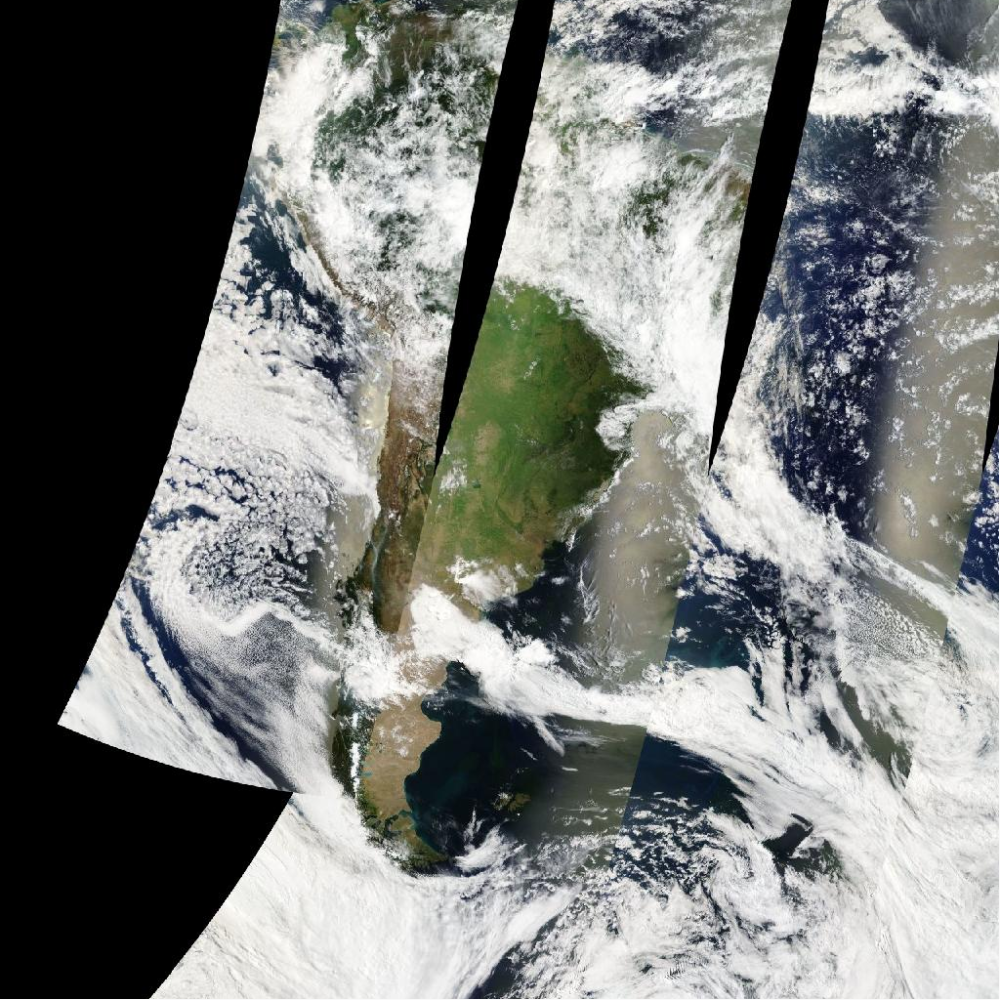

2. Satellites don’t care about zoom levels

Satellite imagery comes in very different forms:

- Geostationary (GOES): whole hemisphere, updated every minutes

- Polar orbiting (MODIS / VIIRS): global coverage, daily cadence

- High resolution optical: city-level detail, slower refresh

Trying to treat all of them like “just another XYZ provider” is where things usually break.

And they did break.

Black images. Strange diagonals. 400 errors. Gigantic rasters copied into tiny buffers.

Each failure exposed an assumption.

3. The key realization: tiles vs reality

The turning point was understanding this:

Some satellite products are already map pyramids Others are raw observations

NASA GIBS is special because it pre-projects satellite data into Web Mercator and publishes it as tiles.

That single fact changes everything.

Suddenly:

- satellite imagery behaves like OSM tiles

- zoom works

- bounding boxes make sense

- you can pan, crop, overlay, analyze

Not by post-processing giant images — but by letting the data source do the hard work.

Example:

require "gd/gis"map = GD::GIS::Map.new( bbox: [-61.0, -32.2, -60.1, -31.4], zoom: 2, basemap: :nasa_terra_truecolor, width: 1024, height: 1024)map.style = GD::GIS::Style.load("solarized")map.rendermap.save("parana_nasa_truecolor.png")4. Making libgd-gis speak “satellite”

Instead of inventing new abstractions, libgd-gis stayed simple:

- a Basemap still returns tiles

- Map still assembles them

- projection math stays unchanged

The difference is conceptual:

basemap: :nasa_goes_geocoloris no longer “a background” but a live sensor feed.

The map is not decoration — it is instrumentation.

5. Multiple scales, one mental model

The same API now supports:

🌍 Continental scale

Cloud systems over South America, updated in near real time.

🗺️ Regional scale

Entre Ríos rendered from satellite true color tiles.

🏙️ Local scale

Paraná city, rivers, islands, vegetation patterns.

All of this:

- same Map

- same bbox

- same zoom

- no special cases in user code

This is the real win.

6. Why Ruby?

Because Ruby is good at thinking.

- fast iteration

- expressive transformations

- glue code between math, images, and ideas

libgd-gis doesn’t try to compete with GIS giants. It sits somewhere else:

between cartography, image processing, and analysis.

7. A new point of view

This is not about “rendering prettier maps”.

It’s about:

- observing floods

- tracking vegetation changes

- understanding soil, water, clouds

- building tools, not screenshots

Once satellite imagery is treated as data, not background, everything changes.

Experiment branch

Seeing Earth from Ruby

The feature/satellites experiment explores how libgd-gis can work with satellite imagery (NASA / GOES) to look at Earth from a completely new perspective — directly from Ruby.

- 🛰 Satellite imagery experiments

- 💎 Ruby-based geospatial workflows

- 🌍 New perspectives on Earth

- 🚧 Work in progress

8. What’s next?

From here, the path is wide open:

- combine GOES clouds with optical imagery

- compute indices (NDVI, water masks)

- detect change over time

- annotate reality, not maps

All from Ruby.

Closing

libgd-gis started as a map renderer.

It quietly became something else:

a way to look at the Earth, programmatically, at any scale.

And once you see that — you can’t unsee it.