January 26, 2026

For many years, Ruby developers working with maps and geospatial data have relied on external tools or loosely coupled pipelines. ImageMagick, command-line utilities, and background processes became the norm, even though they were never designed to be deterministic GIS rendering engines.

The result was fragile systems: slow, hard to debug, and difficult to scale in server-side environments such as Ruby on Rails.

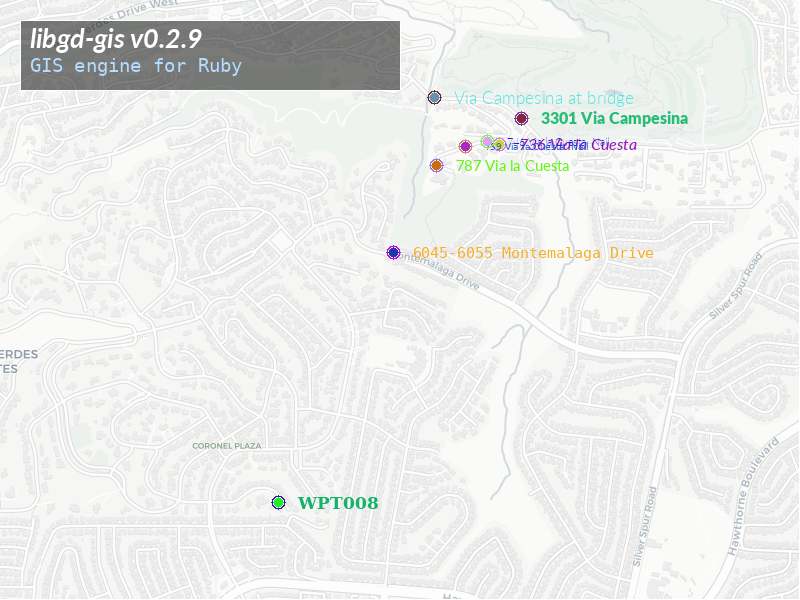

libgd-gis takes a different approach. It is built as a native GIS raster engine for Ruby, directly on top of libgd, with the goal of making map rendering a first-class, in-process capability again. Over the last iterations, the project has moved beyond experimentation and into a phase of stabilization and standardization, laying the groundwork for what could become a future pattern for maps in Ruby.

From experimentation to stability

Early versions of libgd-gis focused on proving that Ruby could once again render maps natively: points, lines, polygons, labels, and raster output without shelling out to external tools. Once that foundation was validated, the main challenge became stability.

Stability, in this context, does not mean “no changes”. It means:

- predictable builds,

- clearly defined APIs,

- consistent behavior across environments,

- and confidence that the same input data produces the same visual output.

To reach that point, the project deliberately slowed down feature development and focused on infrastructure and standards.

A native core that understands formats

One of the strengths of building on libgd is broad format support. At the C level, image decoding and encoding are handled explicitly and deterministically.

A simplified example illustrates the approach:

static VALUE gd_image_open(VALUE klass, VALUE path) { const char *filename = StringValueCStr(path); FILE *f = fopen(filename, "rb"); if (!f) rb_sys_fail(filename); gdImagePtr img = NULL; const char *ext = strrchr(filename, '.'); if (!ext) rb_raise(rb_eArgError, "unknown image type"); if (strcmp(ext, ".png") == 0) { img = gdImageCreateFromPng(f); } else if (strcmp(ext, ".jpg") == 0 || strcmp(ext, ".jpeg") == 0) { img = gdImageCreateFromJpeg(f); } else if (strcmp(ext, ".webp") == 0) { img = gdImageCreateFromWebp(f); } else if (strcmp(ext, ".gif") == 0) { img = gdImageCreateFromGif(f); } else { fclose(f); rb_raise(rb_eArgError, "unsupported format"); } fclose(f); if (!img) rb_raise(rb_eRuntimeError, "image decode failed"); VALUE obj = rb_class_new_instance(0, NULL, klass); gd_image_wrapper *wrap; TypedData_Get_Struct(obj, gd_image_wrapper, &gd_image_type, wrap); wrap->img = img; return obj;}This is not abstracted magic. It is explicit, inspectable behavior. As a result, libgd-gis supports almost all common raster formats for opening and saving, and does so without spawning external processes or relying on shell commands.

That same philosophy is applied at the Ruby level.

GeoJSON as a first-class input

Modern mapping workflows revolve around GeoJSON. Rather than treating it as an edge case, libgd-gis treats GeoJSON as a primary input format.

At this point, almost all GeoJSON structures work as expected, including points, line strings, polygons, and multi-geometries. This makes it possible to feed real-world GIS data directly into a Ruby rendering pipeline, without preprocessing steps or format conversion outside the application.

This is especially relevant for Ruby on Rails applications, where geospatial data often already exists in JSON form.

Docker as the standard build environment

Native libraries fail most often at the boundary between systems. To remove ambiguity, libgd-gis now uses Docker as the reference development and CI environment.

The container defines:

- the Ruby version,

- the exact libgd dependencies,

- compiler toolchains,

- and pkg-config metadata.

This does not replace local development, but it defines the standard. If the project builds and passes tests in Docker, it is considered valid. This eliminates the “works on my machine” problem and makes onboarding contributors significantly easier.

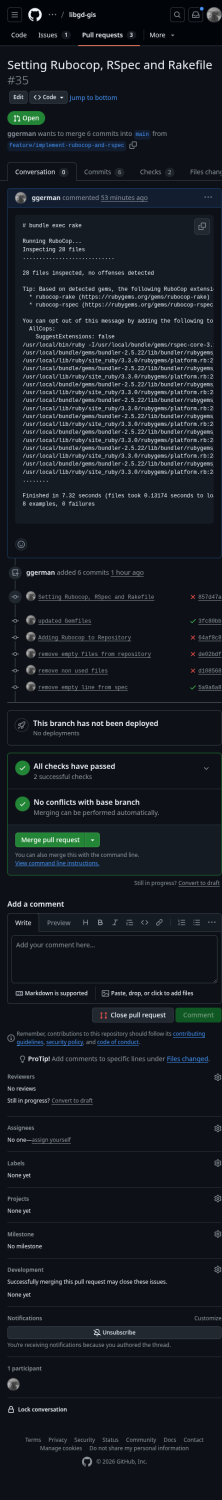

Code standardization without distorting the domain

As the codebase grew, consistency became more important than individual style choices. RuboCop was introduced not to enforce generic Ruby aesthetics, but to define a shared baseline.

GIS and rendering code have characteristics that differ from typical business logic:

- algorithms are dense,

- coordinate math requires short variable names,

- rendering pipelines naturally exceed arbitrary complexity thresholds.

The RuboCop configuration reflects that reality. Metrics that add noise are relaxed, while rules that protect clarity, correctness, and modern Ruby usage remain enabled. The result is a codebase that is consistent without being artificially constrained.

Tests, CI, and confidence

RSpec and CI complete the stabilization loop. Every change is validated against:

- a stable API,

- documented behavior,

- and deterministic output.

A single command is enough to verify the state of the project:

bundle exec rakeIf it passes, the library is in a shippable state. No hidden steps, no environment-specific assumptions.

A future pattern for maps in Ruby and Rails

With these pieces in place, libgd-gis is no longer just a proof of concept. It is becoming a stronger and more scalable foundation for server-side map rendering in Ruby.

The long-term vision is simple:

- native rendering,

- predictable performance,

- direct integration with Ruby and Ruby on Rails,

- and no dependence on external rendering pipelines.

In that sense, libgd-gis is not only a library, but an exploration of what maps in Ruby could look like again when treated as a first-class concern rather than an external service.

Stabilization and standardization are not the end of the journey—but they are what make the next steps possible.