December 23, 2025

Inspired by a talk by Yudai Takada (@ydah) at Hokuriku Ruby Kaigi 01

Advertise on RubyStackNews

RubyStackNews is a niche publication read by Ruby and Rails developers worldwide. Our audience includes senior engineers, tech leads, and decision-makers from the US, Europe, and Asia.

Sponsorship Options

Your brand featured inside a technical article (clearly marked as sponsored).

Highlighted sponsor section embedded within an article.

Logo + link displayed site-wide in the sidebar.

- Highly targeted Ruby / Rails audience

- Organic traffic from search and developer communities

- No ad networks — direct sponsorships only

Interested in sponsoring RubyStackNews?

Contact via WhatsAppRegular expressions are one of the most widely used tools in programming, yet they are often treated as black boxes. We use them daily, but rarely stop to ask a fundamental question: how does a regular expression engine actually work?

In his talk “Walking with Computer Science in Ruby — Building a DFA-based Regular Expression Engine”, Yudai Takada, product engineer at SmartHR and CRuby contributor, takes us on a deep but accessible journey into the internals of regex engines — not by theory alone, but by building one step by step in Ruby.

What “Regular Expressions” Really Mean

Takada begins by clarifying an important misconception: many features commonly called “regular expressions” are not regular in the strict computational sense.

As he explains, regular expressions are:

“A mathematical and computational concept for describing a set of strings using a single notation.”

However, modern engines often include extensions such as backreferences, lookaheads, and recursion — features that go beyond regular languages. Takada references Larry Wall’s famous remark:

“What we call ‘regular expressions’ are only marginally related to real regular expressions.”

This distinction matters, because once we restrict ourselves to true regular expressions, we gain powerful theoretical guarantees — including linear-time matching.

Four Ways to Match a Regular Expression

The talk outlines four major approaches to regex matching:

- DFA-based engines (e.g. RE2, Hyperscan)

- Backtracking NFA engines (e.g. PCRE, Python, Ruby)

- VM / bytecode-based engines

- Regex derivatives (Brzozowski derivatives)

Takada deliberately focuses on DFA-based engines, stating that this approach offers:

“Simple and fast matching with no ambiguity.”

Unlike backtracking engines, DFA matching guarantees O(n) runtime with no catastrophic backtracking.

From Pattern to Machine: The Compilation Pipeline

A key contribution of the talk is its clear explanation of the classic regex compilation pipeline:

Pattern String

↓

Abstract Syntax Tree (AST)

↓

NFA (Non-deterministic Finite Automaton)

↓

DFA (Deterministic Finite Automaton)

Takada emphasizes that regex engines are not magic:

“A regular expression engine is a pipeline that parses a pattern and transforms it into a fast matching machine.”

Each stage serves a purpose:

- The AST removes ambiguity from operator precedence.

- The NFA is easy to construct from the AST using Thompson’s construction.

- The DFA removes non-determinism to enable fast execution.

Thompson’s Construction: Turning Regex into an NFA

Using Thompson’s algorithm, Takada shows how to construct NFA “fragments” for:

- literals

- concatenation

- alternation (a|b)

- repetition (*)

Each fragment has:

- a single start state

- a single accept state

- optional ε-transitions

This compositional approach allows even complex patterns like a(b|c)* to be built recursively.

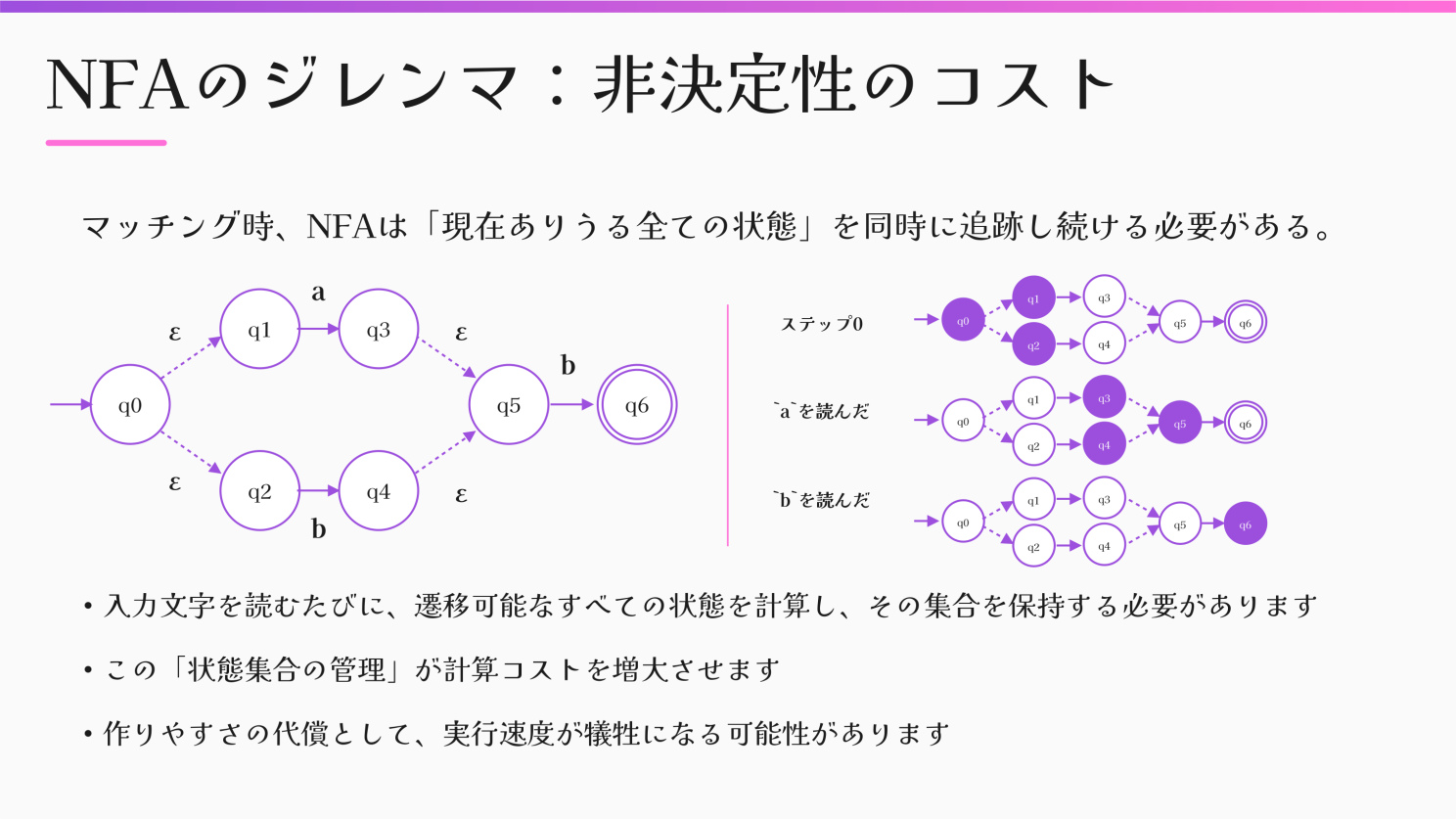

The Cost of Non-Determinism

While NFAs are easy to build, Takada points out their main drawback:

“During matching, an NFA must track all possible current states at the same time.”

This means managing sets of states at every character, which increases runtime cost. To solve this, the engine converts the NFA into a DFA.

Subset Construction: From NFA to DFA

The conversion uses the classic subset construction algorithm:

“One DFA state represents a set of NFA states.”

Key steps include:

- Computing ε-closures

- Generating transitions for each input symbol

- Registering new DFA states

- Marking accept states

- Repeating until no new states remain

Once complete, the DFA has no ε-transitions and no ambiguity.

Matching with a DFA

The final matching algorithm is intentionally simple:

current = dfa.start_state

input.each_char do |char|

current = dfa.transition(current, char)

end

dfa.accept_states.include?(current)

Takada highlights the beauty of this approach:

“Matching becomes simple and fast.”

No recursion. No backtracking. No surprises.

Why Ruby?

One of the most compelling arguments in the talk is why Ruby is the right language for learning this.

Takada explains:

“Ruby allows us to focus on the algorithm itself.”

Compared to lower-level languages, Ruby offers:

- expressive syntax

- powerful built-in data structures (Set, Hash)

- automatic memory management

This makes Ruby ideal for learning computer science concepts through implementation.

Conclusion

This presentation is not about replacing Ruby’s regex engine. It is about understanding.

By walking through the construction of a DFA-based regex engine, Yudai Takada demonstrates that even complex systems can be understood — and built — with clarity, rigor, and elegant Ruby code.

As he humorously concludes:

“Autumn to winter is regex engine season.”

The full source code for the regex engine presented in the talk, named Hoozuki, is publicly available on GitHub and serves as an excellent reference for anyone curious to go deeper.